Abstract:

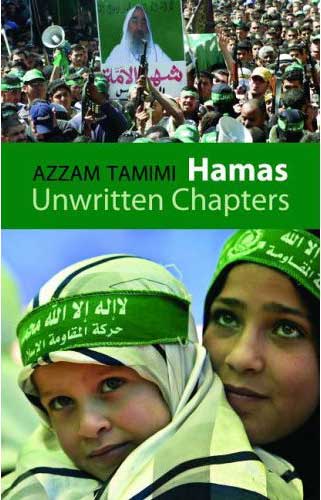

The book under review deals with Hamas, the Islamic resistance movement in Palestine. It deals with a history of the rise of Hamas in the occupied territories, its ideology, its aims and its relationship with other Palestinian movements especially its relationship with the PLO, Fatah and the Palestine Authority (PA). It also includes a discussion on the events up till 30th June 2006 in which the famous election victory of Hamas occurred.

This book is one of a kind. It explains Hamas the movement from its own point of view. The book has been written with the view to explain to the reader what Hamas is, its history and most importantly what it wants. Often in the rush to justify existing power structures that tend to confine a particular group as terrorist etc, the media does not analyze the reasons for the movement to exist in the first place and most important of all its main aim. This is where Tamimi’s book differs from the rest of the literature on Hamas currently available on the shelves of bookshops.

All of these are explained in the 10 chapters and appendices that are all contained within the book. The chapters deal predominantly with the history of Hamas beginning with the 1967 occupation of the remaining third of original Palestinian land by the Zionists up till the sweeping victory of Hamas at the local Palestinian elections of 2004. Other issues, including whether suicide bombing are allowed in Islam and the relationship between Hamas and PLO and other Palestinian groups, are discussed thoroughly by Tamimi.

Hamas: who are they and what is their history? Some as the writer of Freedom Next Time regard Hamas as a CIA invention. Tamimi carefully tracks the birth of Hamas utilizing close interviews with the people involved as well as foreign and Arab news reports. He begins by giving a short history of the Ikhwan (a movement which he is closely connected with) through its influential founder Hassan al-Banna (d.1946). Hassan’s main idea was to “rehabilitate the ummah through gradual reforms” with the aim of reducing and later freeing the Muslim lands from foreign influence and authority towards the effort of establishing an Islamic state within the Islamic homeland. As the Ikhwan became popular, various branches appeared in the Arab world including Palestine. The Palestinian Ikhwan was established after the Second World War and suffered a split when Israel was created in 1948. When Israel invaded the remaining third of Palestine, the Palestinian Ikhwan came together. The leaders for Hamas which came up in the aftermath of the Intifada of 1987 were all members of the Palestinian Ikhwan.

It is indeed baffling that most Western media would portray Hamas as being against the existence of Israel and not agreeing to the two-state solution; the reality is far from it. Hamas believes in the two-state solution and would even adopt a non-violent attitude once this is accepted. The other thorny issue when it comes to Hamas is their suicide bombers and the attacks upon the civilian population. Tamimi notes in chapter 8 of the work, aptly titled ‘Jihad and Martyrdom’ that there are differing views amongst the Muslim scholars in regards to the utilization of this very effective weapon. The views from total acceptance to outright condemnation abound in this sensitive issue. Scholars however point out that Palestine is not involved in conventional warfare therefore the Islamic rules which apply in the usual conventional war are not applicable in this case. The Israelis have invaded the land and occupied it even though it is a clear violation of UN resolutions. Furthermore the civilians on occupied land are not ‘innocent civilians’ as they are all a part of the Israeli military; thus killing them is not killing the innocent. This is the gist of the fatwa given by Qaradhawi. To Qaradhawi and other like-minded scholars, the action of Hamas on occupied land is not governed by conventional warfare. Once the occupation has ended i.e. the Israelis retreat to the 1967 borders, then the suicide bombings will stop. The suicide bombing is just a tool which is used in this unusual situation and cannot be used in conventional warfare.

The relationship of Hamas with other Palestinian organizations is also treated in this volume. Tamimi charts the relations between the two sides from the Oslo accords and gives ample space as to why Hamas is against the peace accords and subsequently the Palestinian Authority. Part of the blame for the failure of the PA has to be put upon the PA itself according to Tamimi. By employing die-hard Fatah activists and former leaders as go-betweens between Hamas and the PA, the discussions held in Amman Jordan back in 1995 fell apart (pg.192-3) and with that the credibility of the PA in the eyes of Hamas’s leaders. Nevertheless Tamimi does give an impression that the leader of the PA Yasser Arafat towards the end of his life had decided to talk to Hamas through Khalid Mish’al probably due to lack of support and increase of enmity between him and his former colleague, the next Prime Minister Mahmud Abbas. Hamas took the side of Arafat against Abbas. Abbas’s renunciation of violence against the Israelis at the Aqaba summit in 2003 and the overt support he receives from the Americans and the Israelis had made him “seem like a puppet for the Americans, installed by them to undermine Arafat” (pg.204).

What were the reasons for Hamas to enter into elections in 2006 when they had boycotted previous elections? The answer to this question lies largely in understanding development of events after the death of Arafat. Tamimi explains the reasons by laying it against a historical reconstruction as well as a description of the socio-political events of Palestine post-Arafat. The reasons as advanced by a member of Hamas Political Bureau, Izzat al-Rishiq were: popular sentiment (pressure?) expected Hamas to participate, the previous elections did not guarantee fair play as it was still under the Oslo era, the decision of boycotting the previous elections was due to Hamas not wanting to fall into the trap of bestowing legitimacy to the Oslo accords. Furthermore according to Tamimi one of the likely reasons is also due to the disappearance of Arafat from the political scene as well as Israel’s unilateral decision to end its occupation of the Gaza Strip on 12 September 2005 (pg. 211) of which Hamas took great credit for. The people had also credited this victory to Hamas and thus made it more popular than Fatah. The lack of leadership of the Palestinian Authority and the disarray of Fatah made Hamas the popular choice of the people. Tamimi is also quick to note that the Hamas boycott of previous elections was not done due to ideological reasons but more political. Hamas, similar to the Islamic movement Ikhwan al-Muslimin, has no problem in power sharing within a democratic system. (It has to be noted that Tamimi has previosuly written a book titled “Power Sharing in Islam” where he puts forward this view. Other Ikhwan figures who believe along the same lines include the London-based Tunisian, Rashid Ghanoushi of whom Tamimi has written a book on as well.)

In his historical reconstruction of the run-up to the elections, Tamimi mentions that there were rumors that Fatah had collaborated with the Israelis in delaying the elections due to its unreadiness to face the elections. Israelis did not want an under-prepared and divided Fatah to face Hamas in the elections as this would enable the latter to win. Israel, which had always fought against the recognition of Hamas internationally, would not want to recognize it locally. This made campaigning for Hamas difficult if not impossible. Furthermore, as a consequence of this policy, Israeli police had closed down three Hamas election offices in East Jerusalem (pg. 217). In the legislative elections that were held on 25th January 2006, Hamas won a resounding victory in capturing 75 seats where Fatah only managed to capture 45. The reasons for this victory are attributed by Tamimi to four main factors: Hamas’s consistency towards the Palestinian dream which is to see all of Palestine free and the return of Palestinians to their homes and lands that were taken in the creation of Israel in 1948. Fatah however had failed miserably in their recognition of Israel (Ironically in their election Manifesto which is available in the Appendix, Hamas had also agreed to a two-state solution with Israel co-existing with Palestine along the 1967 borders). Secondly, officials within Hamas are seen to be more transparent than the corrupt hands of Fatah and the Palestinian Authority. Thirdly Hamas is more Islamic due to its Islamic ideology if compared to the liberal Fatah. Fourthly the failures of the peace process, which had made Palestinian lives more difficult and had aggravated their suffering, were seen to be failures of the former leadership. Instead the withdrawal of the Israelis after 38 years occupation of the Gaza Strip served to further vindicate Hamas and eventually led to this electoral triumph (pg. 220-1).

The relationship of Hamas and Fatah had always been full of ill feelings. Each group on has always believed that the other side had made agreements with the enemy or were invented by the enemy to undermine their group. This view of the other as well as who was responsible for the Intifada back in 1987 are the thorny issues within the Hamas-Fatah relationship. This distrust is what has constantly fueled the hatred which has led both sides to violent confrontation at times, the latest being in the past few months. The recent agreement sorted out by Saudi Arabia between the two groups might evade the bloody street battles but never the hatred which pervades their view of each other. It would require strong will on both sides and their leaders to build trust between them.

The appendices contain 6 original writings by Hamas. Some are translated for the first time in English for the benefit of the reader. They are: “This is what we struggle for”, “The Islamic Resistance Movement”, “We will not sell our people or principles for foreign aid”, “What Hamas is seeking”, “A Just peace or no peace” and the election Manifesto of Hamas “Change and Reform” of January 2006. These appendices give us Hamas’s position on a number of crucial issues such as does Hamas believe in the two-state solution? When will the fighting stop? What is Hamas’s future plan for Palestine? These are the issues which often go unanswered in the media but here the reader will find the answer to these pressing questions. Hamas: Unwritten Chapters is recommended reading for anyone wanting to understand what Hamas stands for and other issues connected to this Islamic movement.

Copyright © 2005 Palestine Internationalist

source: Volume 2 Issue 3, http://www.palint.org/article.php?articleid=32

The opinions expressed on this site, unless otherwise stated, are those of the authors.